Hiatus Hernia

What is a hiatus hernia and why they are important when considering reflux treatment

Enquire about Hiatus Hernia

Hiatus Hernia

Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD) can be either primary or secondary. In other words, other conditions can cause reflux in which case it is secondary. An example would be gastroparesis, in which the valve that normally prevents reflux from the stomach into the oesophagus (Lower Oesophageal Sphincter or LOS) is normal but the stomach doesn’t empty normally and so pressure builds up within the stomach overcoming the strength of the valve. Another secondary cause is obesity where the pressure in the abdomen exceeds that of a normal LOS.

Mr Boyle recommended an endoscopy, this showed I had a sliding hiatus hernia

Make an enquiry about Hiatus Hernias

Looking to diagnose a possible hiatus hernia? Or looking for treatment steps following diagnosis?

Hiatus Hernia EnquiriesWhat is the LOS?

The oesophagus passes through the chest and into the stomach which sits in the abdominal cavity. The chest and abdomen are separated by the diaphragm, a large flat muscle that helps us breathe. The hole in the diaphragm through which the oesophagus passes is called the “hiatus”, meaning an opening or aperture from the Latin verb “hiare” which means to gape or yawn. When we swallow food, it is pushed down the oesophagus by co-ordinated muscular contraction in its wall and when it reaches the bottom the LOS opens to allow passage into the stomach. It then closes behind the food bolus to prevent reflux. This process obviously requires co-ordination.

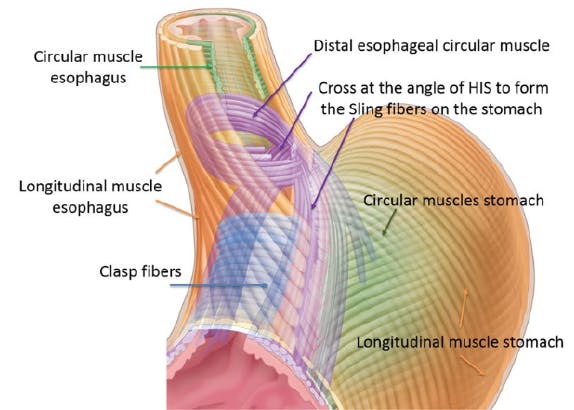

The LOS is a very complicated physiological mechanism. There are several factors that contribute to the valve’s strength including the shape of the junction between the oesophagus and stomach and the fact that normally there is a short section of oesophagus below the diaphragm. There is no obvious thickening of muscles at the bottom of the oesophagus as there is in other valves along the GI tract, for instance at the bottom of the stomach at the pylorus. However, the muscles at the bottom of the wall of the oesophagus are orientated as a “sling” and these contribute about 50% of the strength of the valve.

What is not generally appreciated is that the muscles of the diaphragm around the hiatus contribute the other 50%. Anatomically they can vary in configuration but there are generally two each called a “crus” and together these are known as the “crura”. It’s equally important to appreciate that the hiatus isn’t just a hole in the diaphragm. The crura are orientated a little bit like a funnel or sling around the oesophagus as it passes through the diaphragm for 2-3cms. Compression by the muscles of the crura is a fundamental component of the LOS mechanism and they are essential to prevent reflux and their relaxation equally important to facilitate swallowing.

The muscles of the crura are supplied with a different nerve supply to the muscles in the oesophagus and these supplement and coordinate with each other in responding to differences in pressure within the oesophagus, stomach, chest and abdominal cavities. The nervous supply co-ordinates both relaxation to allow swallowing and contraction to prevent reflux. Anything that disrupts the normal nervous or muscular activity in either the oesophagus or crura or changes the orientation/approximation of the crura around the oesophagus will pre-dispose to reflux.

Reflux can occur without a hiatus hernia. The reasons aren’t always identified but it is associated with other conditions which affect the nerves or muscles. It might even be caused by infections causing damage to the nerves that supply the oesophagus or crura.

Hiatus Hernia

When a hiatus hernia evolves most people will develop reflux although they can be asymptomatic. Hiatus hernias are probably the main cause of GORD as they cause failure of the LOS.

What is a Hiatus Hernia and how do you get one?

What is the meaning of a 'hiatus hernia'? Firstly, a definition. A hernia occurs when an organ, or part of an organ protrudes through connective tissue or a wall of the cavity in which it is normally enclosed. So, a hiatus hernia occurs when part, or very occasionally all of the stomach protrudes through the hiatus of the diaphragm from the abdomen where it is normally situated, into the chest. Like most hernias, the stomach usually moves up and down through the hiatus so that sometimes it sits in its usual position and at others abnormally.

Hiatus hernias are caused by a degenerative disease. A hiatus hernia occurs when the soft tissues around the crura and the muscles themselves become weak. Research has shown that there are often identifiable biochemical and associated genetic abnormalities in the tissues around the crura that cause them to deteriorate. This may well be why hiatus hernias and reflux often are passed between generations within families. As a consequence of these weaknesses the usual connections between the crura and the oesophagus decay and in due course the gap between the crura, the hiatus, enlarges. As this occurs, since the muscles of the crura are no longer closely applied to the oesophagus the pressure that the crura are able to exert on the oesophagus inevitably reduces and inevitably the LOS becomes weaker.

In a hiatus hernia the stomach moves up and down between the abdomen and chest cavities. Secondly, the stomach is no longer held below the diaphragm and is able to pass between the crura of the hiatus moving up and down between the abdominal and chest cavities. The pressure difference between the stomach and oesophagus is therefore compromised and this contributes further to the deterioration of the LOS even further. At first only the top of the stomach will move up and down. However, the process tends to be progressive and slowly worsens over time and as it does so the size of the hiatus hernia will increase. This size is measured during an endoscopy in centimetres which reflects the distance that the top of the stomach has moved above the hiatus. Generally, up 2-3cms would be considered small and 3-6 moderate, although this distinction is arbitrary especially in terms of symptoms. In giant hiatus hernias the entire stomach can move to sit within the chest. Symptoms often don’t reflect size and small hernias can cause more symptoms than large ones. From a technical perspective hiatus hernia are divided into 4 types.

Types of Hiatus Hernia. In type 1 or “sliding” hiatus hernias which are by far the most common, the stomach and oesophagus “slide” up into the chest through the hiatus. In type 2 “rolling” hiatus hernias which are rare, the oesophagus doesn’t move but the stomach rolls up into the chest beside the oesophagus; these in particular can cause pain as well as reflux symptoms. In type 3, or para-oesophageal hernias both stomach and oesophagus move up into the chest and in some cases which develop over time the whole stomach can end up in the chest. Type 4 are rare and include other organs from the abdomen such as the small bowel, colon or pancreas. In Types 2, 3 and 4 in addition to reflux the stomach may twist (volvulus) or become stuck in the chest (incarceration) causing difficulty eating or even acute pain and “strangulation” when it suddenly loses its blood supply causing a surgical emergency. This is rare but an occasional cause of death.

Types of Hiatus Hernia

Note that in type 1 hernias both the bottom of the oesophagus and top of the stomach “slides” through the hiatus up into the chest. In type 2 the oesophagus doesn’t move but the top of the stomach “rolls” alongside it up into the chest. In type 3 there are both rolling and sliding hernia components.

Hiatus Hernia and reflux - how do Hiatus Hernias cause reflux?

These images illustrate that once a hiatus hernia develops there is a serious bio-mechanical problem. Once the sling fibres of the oesophagus are no longer augmented by the crura, the LOS almost always becomes weak and incompetent. At first symptoms may only occur when the LOS is stressed, for instance after large meals when the pressure in the stomach is raised or at night when gravity is no longer helping to keep gastric contents within the stomach. As the hernia gets bigger, more of the stomach is exposed to the negative pressure in the chest and since the crura can no longer contribute to the strength of the LOS it will increasingly fail causing worsening symptoms perhaps with regurgitation of food into the throat and mouth.

What is the treatment of Hiatus Hernias and why is repair of Hiatus Hernias so important?

A hiatus hernia is a degenerative bio-mechanical failure. Once this is understood it is clear that life-style changes and medications can only control symptoms and cannot solve the fundamental anatomical problem. An analogy would be to use anti-inflammatory drugs or physiotherapy to help the pain associated with arthritis of the hip or knee. Non-surgical options can certainly help symptoms and will avoid surgery for some, but ultimately joint replacement is so commonly employed because it fixes the problem. That’s not to say that all hiatus hernias require surgery, far from it. However if symptoms are not controlled by medications then surgery will offer the best chance of long-term control. In this context the aversion to surgery and insistence on employing medications to the exclusion of considering surgery by some doctors is strange.

The LOS relies on the crura. Without repair it won’t work properly. This is supported by published evidence from clinical trials that has shown that once patients develop regurgitation, high dose antacids including PPIs will control symptoms in only about 10% of patients whereas surgery is effective in 90%. Whether LINX® or Fundoplication, repair of the hiatus and re-approximation of the crura around the oesophagus are an essential component of any successful operation. “Crural repair” is easily performed by stitching the muscles of the crura together and bringing them back into close approximation with the oesophagus. Indeed, other scientific studies have also been published which have measured the contribution to the pressure exerted by the LOS during surgery by crural repair and then either fundoplication or LINX. These have shown that the crural repair adds 50% of the final strength of the LOS after reconstruction, which isn’t surprising as we’ve known for years that the contribution of the oesophageal muscle and crura to LOS pressure are about equal.

This explains the answer to the question that many patients ask; can I just have a LINX without repairing the hiatus hernia or crura? It also explains why endoscopic procedures such as TIF®️ that don’t include reduction of a hiatus hernia and crural repair don’t tend to work as well as surgery as they address only part of the biomechanical problem.

In the presence of a hiatus hernia we would advise that LINX or fundoplication is more likely to achieve a good result in terms of reduced reflux symptoms than other interventions.

What about recurrence after surgery?

Hiatus hernias are a degenerative and progressive condition. The weakness in the soft tissues around the hiatus pre-dispose to their development in the first place. Without intervention their natural history tends to be gradual increase in size over many years. However, this course is unpredictable, and we don’t know why some people develop giant hiatus hernias and others don’t.

After anti-reflux surgery hiatus hernias have a tendency to recur in some people. Indeed, after fundoplication at 5 years 25-50% of patients will have recurrent symptoms requiring PPIs and about 10% of patients will need to undergo revisional surgery. We don’t know for sure as yet, but it is thought that the scar tissue that naturally occurs around the LINX device once it is implanted helps to anchor the oesophagus in the right position below the diaphragm and that this may help prevent recurrence of hiatus hernias and reflux in the years following surgery.